The Duty to Consult with Aboriginal Peoples: A Patchwork of Canadian Policies

Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution states that “the existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed”. In an attempt to provide greater clarity the constitution defines “treaty rights” as rights that now exist by way of “land claim agreements or may be so acquired”. It is through this constitutional provision that the duty to consult has been constructed by Canadian courts. The department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada estimates that the legal duty to consult is triggered for some provinces over 100,000 times per year and for the federal government over 5,000 times per year.

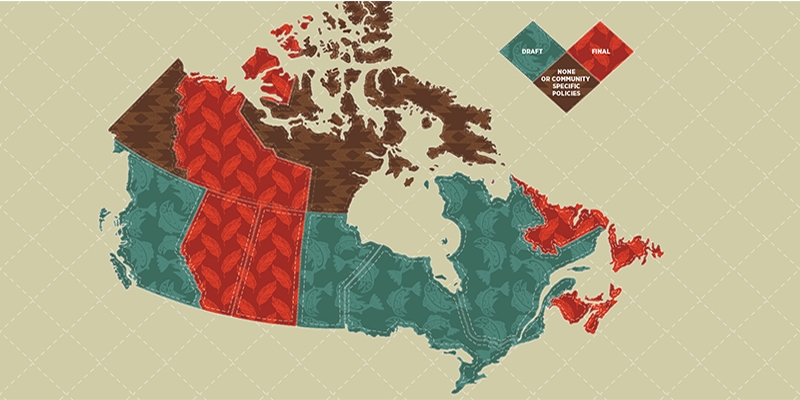

Over the past decade, the Supreme Court of Canada has attempted to define how provincial and federal governments are to put into practice their duty to consult with First Nations. They have done this through various judgments including: Haida Nation v. British Columbia, Taku River Tlingit First Nation v. British Columbia, Mikisew Cree First Nation v. Canada, and Tsilhqot’in Nation v. Canada. In an effort to address the Crown’s legal obligation to consult with aboriginal groups, provinces have created consultation guides for their departments and project proponents. However, these guidelines are vastly different depending on which jurisdiction a project is in. This creates a patchwork of consultation policies across the country.

There are some principles that all jurisdictions share, such as the Crown’s taking responsibility for the duty to consult; and yet there are other principles that differ dramatically depending on the province in which a project is located. For example, British Columbia, Manitoba, and Quebec are the only jurisdictions that do not state in their policies that aboriginal communities are required to participate in the consultation process. British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec also all still have “draft” aboriginal consultation policies. In the case of Ontario, their policy has been in draft form since 2006. The consultation process could be improved for project proponents and First Nation communities across the country.

Recommendations

- British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec could provide additional certainty to First Nations and project proponents by finalizing their “draft” consultation guidelines.

- British Columbia, Manitoba, and Quebec could outline the roles and responsibilities of First Nations during the consultation process. The rest of the jurisdictions analyzed for this paper have clear expectations of engagement from First Nations communities.

- Timelines around the consultation process to ensure the duty to consult is implemented in a timely way is another improvement jurisdictions could adopt. Timelines will help guide project proponents who are undertaking procedural aspects of the duty to consult and it will also provide First Nations a clear indication of how long they have to engage in the consultation process. First Nations’ capacity to engage in the consultation process should be taken into consideration when developing timelines.

- Manitoba could improve their process by including clear offloading provisions in their duty-to-consult policy and highlighting what, if any, procedural duties can be offloaded to project proponents in the consultation process.

Authors:

More from this study

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.