Year-end facts about the federal government’s performance in 2021

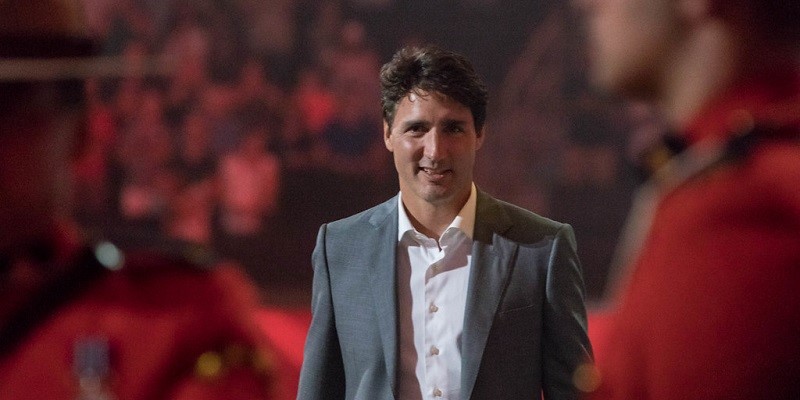

To hear Prime Minister Trudeau and Finance Minister Freeland tell it, everything is rosy with Canada’s economy. Indeed, Minister Freeland recently said Canada is “ready, as a country, to come roaring back.” That’s good rhetoric, but what about the facts? As 2021 ends, here are a few year-end facts Canadians should understand.

For starters, the government forecasts inflation-adjusted economic growth at 4.0 per cent in 2022, 2.1 per cent in 2023, 1.9 per cent in 2024 and 1.8 per cent in 2025. That’s not exactly “roaring back”—more like a positive bump followed by a fizzle.

And in fact, the Canadian economy has been underperforming for more than a decade. A recent study by Philip Cross, former chief analyst at Statistics Canada, found that economic growth has been lower over the past 10 years than in any decade since the 1930s. Before COVID, Canada ranked near the bottom among advanced countries (30th out of 38) on average economic growth from 2015 to 2019.

During COVID, things didn’t get any better. In 2020, as Prof. Livio Di Matteo’s study Global Storm explained, Canada had the 25th worst economic performance and fourth-highest unemployment rate among 35 advanced countries—despite the fact Canada was the second-highest spender with the highest deficit-to-GDP ratio.

Then there’s Canada’s inflation rate, which for 2021 is expected to rank sixth-highest of the 35 advanced economies. We’re also expected to have the eighth-highest unemployment rate. On the so-called Misery Index, determined by the inflation rate combined with the unemployment rate, Canada ranks sixth most “miserable” among 35 advanced economies.

But there’s always next year, right?

Well, in 2022, according to OECD forecasts, Canada’s economic growth will rank 21st of 38 countries, despite Ottawa’s ongoing stimulative spending. Looking further out, the OECD predicts Canada will be the worst-performing advanced economy from 2020 to 2030, with inflation-adjusted per-person GDP growth of only 0.7 per cent per year over the decade, due in part to our sluggish rate of private-sector investment.

As Prof. Steven Globerman’s recent work finds, Canada’s growth rate of overall business investment dropped from 44.8 per cent in the five-year period of 2000 to 2005 to 25.1 per cent (2005 to 2010), to 18.9 per cent (2010 to 2015) and to 11.6 per cent (2015 to 2019)—among the slowest growth ever recorded in the past 50 years (and remember, this decline is pre-COVID). Furthermore, in the five years before COVID, seven of 15 Canadian industries experienced an overall decline in investment.

Unfortunately, poor policy decisions, particularly by our federal government, have fuelled these dismal economic results. While policymakers could reduce our relatively high marginal tax rates and make Canada’s tax system more supportive of entrepreneurial risk-taking, they’ve done the opposite. The Trudeau government increased the top federal tax rate from 29 per cent to 33 per cent. The top 20 per cent of income-earning families now pay nearly two-thirds (63 per cent) of Canada’s personal income taxes.

Let’s also not forget that the Liberals have mused about increasing the capital gains tax and that Finance Minister Freeland has supported the idea of a new wealth tax. Incidentally, the Liberal minority government needs a partner to help pass the 2022 budget and the NDP campaigned on both a new wealth tax and a higher capital gains tax.

Then there’s the national debt, expected to reach $2 trillion by 2025-26. Prime Minister Trudeau and Finance Minister Freeland seem to ignore the fact that debt has costs. But a recent study found that Canadians aged 16 to 25 can expect to pay an additional $118 billion ($20,000 each) in personal income taxes over their lifetimes to pay the higher annual interest payments on federal debt accumulated from 2019 to 2025. This does not include the additional tax burden required to actually pay the $686 billion in federal debt expected to be accumulated over that time, nor the $2 trillion in outstanding debt expected as of 2025. Both the prime minister and finance minister repeatedly claim that Canada’s government debt compares favourably to international counterparts. But that’s simply not true. Canada’s total government debt relative to GDP is the fifth-highest out of 29 advanced countries.

Finally, Canada is pursuing climate policies that will do more harm—through economic and social costs—than good. For example, Ottawa’s $170 per tonne carbon tax, which the government claims will have “almost zero” impact on the economy. However, Prof. Ross McKitrick’s study found that the carbon tax will lead to 185,000 jobs lost nationwide and a massive $38 billion decline in GDP.

Higher tax rates, increased regulation, a massive new federal carbon tax and deteriorating government finances have made our country much less attractive for entrepreneurs and investment, and have reduced economic growth rates.

As 2022 begins, let’s hope we see a refocus on policies that will actually improve the economy and the lives of Canadians.