William Watson: About that $8 cauliflower—locavoring probably won’t help

These days Canada is known—even CNBC had a story about it—as the country of the $8 cauliflower. I haven’t actually seen an $8 cauliflower, being only an occasional cauliflower purchaser myself. But the “white gold” problem, as it’s called, is symptomatic of rising food prices generally. What we’re gaining in lower gas prices we seem to be losing in higher food prices.

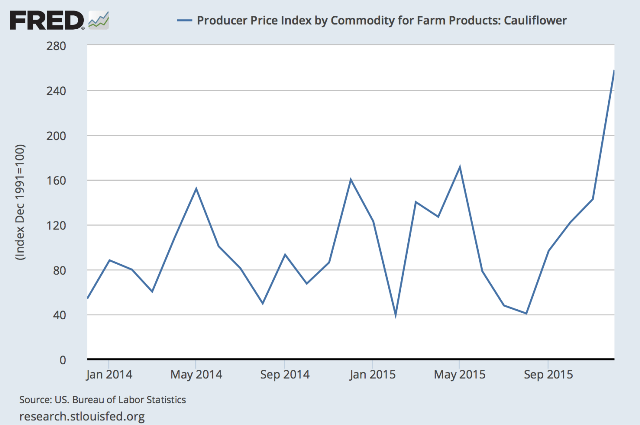

We tend to think the cauliflower crisis is uniquely Canadian but as the below graph from the St Louis Fed “FRED” database shows, the problem is at the U.S. farm gate. While it has been a mild winter in eastern Canada, California has been unseasonably cold. Plus cauliflower plantings were down a bit to begin with. As a result, though the American cauliflower price index has been cycling around 100 for the last couple of years, the latest data (for December) show a spike to 257.9. Add a plummeting Canadian dollar to that and you get $8 cauliflower.

Is that a disaster? If you love cauliflower, it is. But I suspect most people don’t really love cauliflower so it probably isn’t.

Are higher prices for all imported foods a problem? Sure, they are. TV news always stresses the advantages of a lower dollar for Canadian exporters. But though only some of us export, virtually all of us import.

How big a problem is it? Food’s weight in the Consumer Price Index is 16.41 per cent, down from as high as 17.99 per cent in 1992. As we’ve gotten richer (and we have) food has declined as a share of our spending. StatsCan doesn’t actually provide a weight for cauliflower but fresh fruit is 0.9 per cent of the average consumer’s spending and fresh vegetables 1.06 per cent. Meat is the biggest food item at 2.28 per cent. If the prices of these items rise sharply, that’s clearly going to have an effect. But let’s keep things in perspective. On average, food just isn’t that big a part of the average Canadian’s budget. (By contrast, looking at the other classic necessities, shelter is 26.8 per cent and clothing and footwear 6.08 per cent.)

Some people have argued that high prices for food imports, whether because of the low dollar or other factors, will boost local food growers, many of whose costs are incurred in Canadian dollars. So long as the high prices last that seems bound to be true. But will that really bring local food prices down? When goods are or can be traded, their price is set on international markets. Local food producers may be touch-feely-green-granola types, but if the imported price of what they’re growing is high, they may well end up selling it at the world price, which from our window on the world is usually the U.S. price. Cross-border trade goes both ways. If U.S. food prices are so high they enable Canadian production of fruits and vegetables where it wasn’t before, nothing prevents the Canadian produce from heading south if the price is better.

It will be an interesting test of whether local farmers are wed to communitarian values or are as susceptible to economic self-interest as the rest of us. I’m betting they respond as economic—not communal—theory predicts.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.