Spending, not lack of revenue, driving Ottawa’s red ink

As budget season approaches in Ottawa, attention will turn—for a moment, at least—to what the Trudeau government projects for federal revenues, expenditures the deficit and the debt. This government can already lay claim to the two highest-spending years in Canadian history outside of major war or recession. And it already projected a $19.6 billion deficit for 2019-20—that’s during good economic times without a recession, which that would generate an even higher deficit.

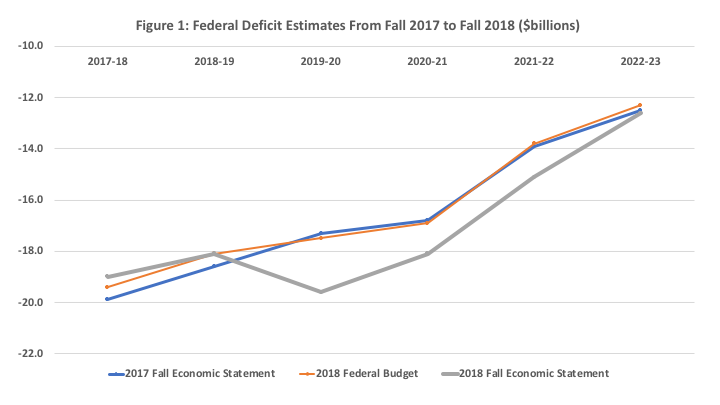

The best indication of what’s coming in the 2019 spring budget is the 2018 Fall Economic Statement, given that Budget 2018 closely mirrored the 2017 Fall Economic Statement. The chart below lays out assorted estimates of the federal deficit between 2017-18 to 2022-23 as provided in the 2017 Fall Economic Statement, the 2018 Budget and the 2018 Fall Economic Statement.

The biggest changes are in the 2018 Fall Economic Statement deficit from 2019-20 to 2021-22, which see an additional deficit accumulation of $4.6 billion on top of the $52.8 billion already laid out in Budget 2018. All the estimates converge to a deficit of more than $12 billion by 2022-23.

Of course, the claim will be made that these deficits are justified as part of strategic investments in growing Canada’s middle class or meeting future infrastructure needs. But these large deficits are really just increases in current spending. While the Trudeau government announced $95.6 billion in infrastructure funding in two phases, it’s spread over 11 years with only a fraction of that amount reflected in current deficits. Much of the spending reflects a host of initiatives designed for a more “equal, generous and sustainable Canada” alongside increased transfers to individuals and provinces.

When the 2019 Fall Economic Statement projections are examined in more detail, the numbers are troubling. Between 2017-18 and 2022-23, total tax revenue is expected to rise from $263.1 billion to $315 billion for an increase of nearly 20 per cent. There’s certainly not a dearth of future revenues based on those numbers. In other words, there’s not a revenue problem.

At the same time, total program spending is projected to rise from $310.7 billion to $359 billion for an increase of 16 per cent, but debt-service costs are expected to go from $21.9 billion to $32.7 billion for an increase of almost 50 per cent.

It would appear that after years of historically low interest rates, the revenge of compound interest is on the horizon with debt-service costs becoming increasingly important as an expenditure driver for the federal government.

As for other spending, over the same period, the 2019 Fall Economic Statement forecasts transfers to individuals rising from $93.8 billion to $116.7 billion—a 24 per cent increase. And transfers to other governments from $70.5 billion to $85.1 billion—a 21 per cent increase. Both increases are larger than the tax revenue growth.

In the end, the big driver of federal spending during a time of relative economic prosperity is transfers—be they transfers to individuals, transfers to other governments or transfers to bondholders. And again, transfers are growing faster than revenues.

One could understand multi-billion dollar deficits if the economy was in a recession and in need of fiscal stimulus. One could see a need for deficit-financing if large amounts of borrowing were needed for major national transportation infrastructure projects to foster energy exports or boosting Arctic security in the face of challenge or danger.

But Ottawa is running large deficits, not to deal with an economic downturn or as part of any strategic investment mandate. It’s just spending a lot more than it takes in.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.