Minimum wage hikes can hurt the people they’re supposed to help

Recently, Premier Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservative government said it will not proceed with a scheduled increase to Ontario’s minimum wage, which the previous government planned to implement next year. As a result, the minimum wage will stay at its current level of $14 per hour, rather than rising to $15 per hour.

Although proponents of a higher minimum wage have criticized the Ford government’s decision, evidence suggests that further increasing the minimum wage would not have significantly reduced poverty in the province (as claimed by proponents) and, what’s more, would have made it more difficult for young and less-skilled workers in Ontario to find work.

Let’s start with the question of poverty.

Proponents of a higher wage floor frequently state their desire to reduce the number of people living in dire economic circumstances. But there’s precious little evidence to support claims that the minimum wage is an effective tool for achieving this end. Several recent studies have analyzed the impact of higher minimum wages on poverty and have failed to find evidence that higher minimum wages put any measurable dent in the problem.

So, there’s a glaring paucity of evidence suggesting that the minimum wage achieves its central stated objective of reducing poverty. But why?

The answer to this question is straightforward, though perhaps will come as a surprise to some. The vast majority of minimum wage workers don’t live in low-income households. In fact, most minimum wage workers are secondary or tertiary earners in households below Canada’s official low-income cut-off line—known as the LICO.

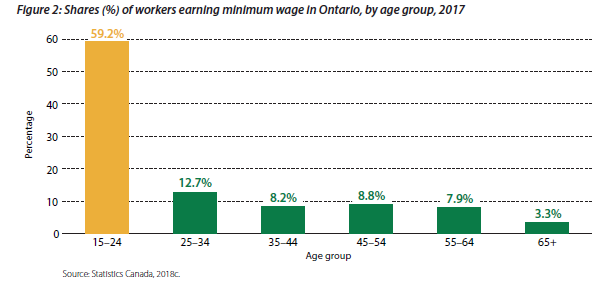

More specifically, in the last year of available data (2017) a clear majority of minimum wage workers were young Ontarians between the age of 15-24. As the chart below shows, 59.2 per cent of all minimum wage earners belonged to this category in 2017.

This share has almost certainly fallen in 2018 due to the increase to the minimum wage, but the important fact remains—minimum wage work is in large measure the province of young people just getting started in the workforce, many of whom live in households that are not in low-income, thanks to labour income earned by their parents or other relatives.

This reality underscores the limitations of the minimum wage as an anti-poverty tool. Even if there were no negative effects on employment, raising the minimum wage another dollar wouldn’t put a substantial dent in poverty largely because much of the extra labour income would flow to households that already aren’t poor.

And the negative employment effects from minimum wage increases are no small concern.

A substantial body of research in Canada consistently shows there can be meaningful negative effects on employment, as business hire fewer people while not adding hours they otherwise would have to work plans because they chose to invest more of finite resources in other inputs to their production processes.

So again, not only does raising the minimum wage fail to effectively target low-income households, it also can make matters worse for some Ontarians (specifically young and less-skilled ones) by making it harder for them to find gainful employment or even part-time work.

The Ford government will likely take some political heat for not moving ahead with another increase to the minimum wage (on top of the 20 per cent hike that took place at the start of this year). The evidence, however, clearly suggests that the Wynne government’s plan to tack another dollar onto the minimum wage would have done little to reduce poverty and actually would have made it harder for some Ontarians to move up the employment ladder.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.