Look to 1990s welfare reform to help fix Canada’s health-care system

The Liberal government in the mid-1990s under Prime Minister Jean Chretien and Finance Minister Paul Martin is remembered for slaying a massive budget deficit that threatened Canada’s financial future.

The 1995 budget was a watershed moment that unleashed a wave of policy reforms that helped repair the country’s finances. One of the most important reform initiatives in that budget was the restructuring of federal transfers to provincial governments.

Specifically, the transfer reform of the 1990s significantly reshaped the relationship between the federal government and the provinces with respect to welfare policy. The history of welfare reform during that era in particular holds lessons for today, primarily for Canada’s ailing health-care system.

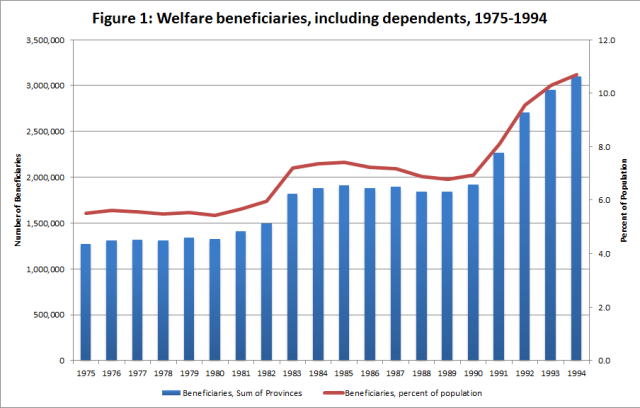

First, a little historical context. In the early ’90s, provincial welfare programs across the country were experiencing growing rolls and rapidly escalating costs. As the chart below shows, the number of welfare recipients had more than doubled since the early 1980s, creating a significant strain on public finances in the provinces.

Predictably, this increase in welfare recipients meant a big increase in costs. By 1994, the share of provincial expenditures dedicated to welfare had climbed to seven per cent from five per cent in 1981.

Growing welfare rolls and costs were a problem for provincial governments, which were severely limited in their ability to address those problems. Why? Because up until the 1995 budget, federal government transfers to the provinces came with a number of conditions that dictated the design of provincial welfare programs. For instance, if any province required recipients to work in order to receive welfare payments, the federal government could withhold the transfer money.

This situation fundamentally changed with the 1995 budget. In that budget, the federal government replaced existing transfers for social welfare and health-care funding with the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST). The CHST was $4.1 billion less than existing transfers when fully phased-in in 1997/98, but the federal government reduced taxes, which gave the provinces the option to generate more revenue to make up the difference. Crucially, the CHST eliminated strings that were attached to welfare transfers (but not health care).

With the freedom to innovate, provinces experimented with a wide range of welfare reforms. The results were remarkable.

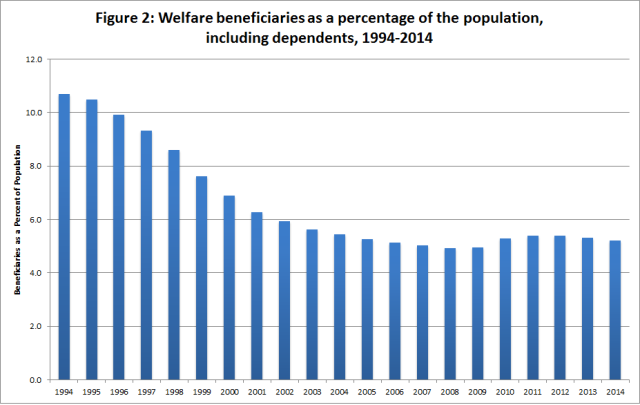

The chart below shows the decline in welfare beneficiaries beginning in 1995. The percentage of the population receiving welfare benefits plunged from 10.7 per cent in 1994 to 6.3 per cent in 2001 and continued to decline to a low of 4.9 per cent in 2008. The ratio has not been above 5.4 per cent since.

The decline in beneficiaries led to a decline in the percentage of provincial program spending dedicated to welfare, from 7.0 per cent in 1994 to a low of 3.9 per cent in 2008.

Of course, if this had just resulted in less people receiving welfare without a change in employment levels, the reforms could have been problematic. However, the wave of provincial welfare reforms coincided with an increase in employment.

The successful history of welfare reform in Canada provides some useful lessons for improving outcomes in other policy areas such as health care. Giving provinces more autonomy to design programs tailored directly to the needs of their own populations can result in better outcomes than one-size-fits-all program designs imposed by the federal government.

Authors:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.