If we’re not ready, immigration comes with heavy costs

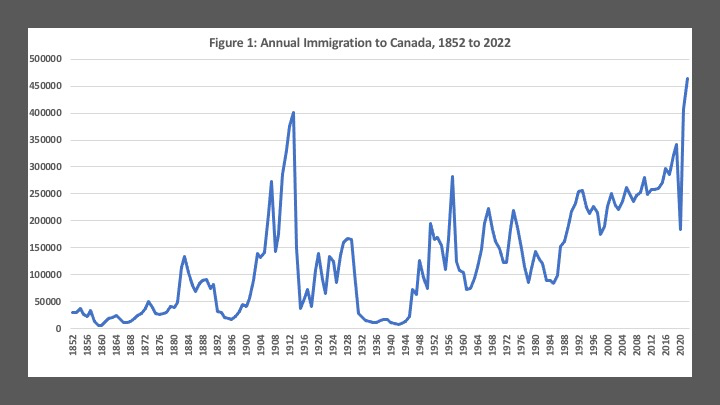

Welcoming more than 500,000 immigrants a year by 2025 has raised concerns of whether we can keep up, especially with housing infrastructure. There’s also the question about whether immigration is the economic driver it’s been touted to be, and its potential for diminishing returns. Nevertheless, 406,000 immigrants in 2021 was the highest total since 1913 (which was 400,900) and 2022 hit 431,645.

The first chart below plots annual immigration to Canada going back to 1852 (with 1852 to 1866 really just immigration to Ontario and Quebec—then known as the Province of Canada).

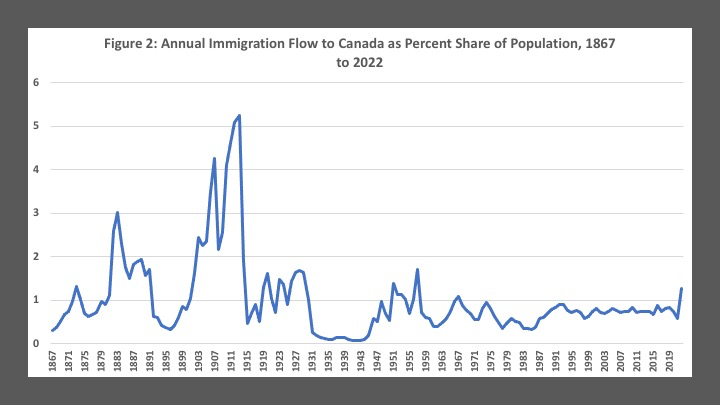

The high absolute totals notwithstanding, the current migration boom is actually rather modest by historical standards when considered as a share of population (as illustrated in the second chart covering 1867 to 2022).

Annual immigration presently represents slightly more than 1 per cent of our annual population. Previous boom eras saw annual migration flows peak at 3 per cent in 1883, 4 per cent in 1907, 5.1 in 1912 and 5.3 per cent 1913—the largest peaks (again, as a share of the population) at the time.

The equivalent today would mean nearly 2 million immigrants a year—four times our target by 2025. The anticipated boom as a share of population is actually rather modest by historical standards and more likely to resemble that of the 1920s or 1950s, but our ability to deal with this level of immigration today is the key in question.

The composition of our immigration has changed, with earlier waves emphasizing unskilled labour that went into our resource and goods-intensive industries. Our current system with its point system emphasizes high-skilled and educated labour in demand in our more service and knowledge-intensive economy. An unskilled immigrant to Canada in 1912 arrived during a national development and construction boom driven by Prairie settlement with a soaring national investment-output ratio at upwards of 30 per cent of GDP. Then, a new arrival if desired and willing to move out west, could also expect to receive a land grant of hundreds of acres of prairie land.

Today’s more skilled and educated immigrants face a different environment. While their services as skilled workers are in demand given the national labour shortage, they face high housing prices, goods and services shortages, more than $2000 a month rent for a one-bedroom apartment, crowded roads and limited public transit. Today, we seem to struggle to maintain our crumbling infrastructure, and our investment-output ratio has been in the doldrums for decades languishing at slightly more than 20 per cent of GDP. Without accompanying business investment, increasing our labour supply will lead to diminishing returns and lower per-capita income growth. And much of the immigration is still coming to three key areas—Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal—further taxing infrastructure in those cities.

Immigration has its benefits. But immigration, which expands beyond the capacity of the economy to accommodate it, comes with costs. That’s the real challenge we face. Solving labour shortage issues rooted in an aging population with a quick-fix immigration boom—absent a credible ability to expand capacity and infrastructure and business incentives—is a short-sighted “let them come and hope we build it” philosophy. We don’t do ourselves or—newcomers, for that matter—any favours.

The solution is to ramp up our ability to accommodate needed immigrants as we’ve been able to in the past.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.