Ontario stuck in vicious cycle of deficits and debt accumulation

After a pandemic-induced delay, Ontario will release its provincial budget this Thursday and Finance Minister Rod Phillips has already said the budget will focus on COVID response measures.

Earlier, the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario issued its fall 2020 economic and budget outlook with a 2020-21 deficit forecast of $37.2 billion, which is remarkably close to the provincial government’s own 2020-21 first quarter finances estimate of $38.5 billion.

First, let’s put this record provincial budget deficit in historical context. The pandemic is really the latest in a set of circumstances that have fostered long-term deficits and more debt accumulation in Ontario.

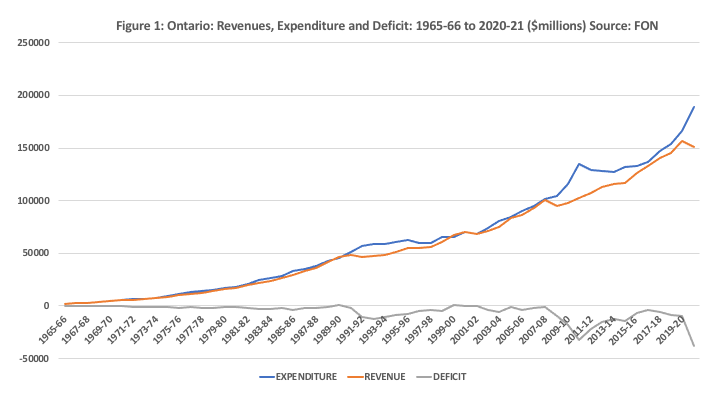

The first chart below presents Ontario’s total revenue, total expenditures and deficits from 1965-66 to 2020-21.

Over this period, total spending grew from $2.1 billion to $189.2 billion while revenues increased from $2.1 billion to $150.6 billion. Revenue and spending have grown in tandem but more often than not spending has exceeded revenues. Indeed, over this 56-year period, Ontario has run a deficit in 51 out of 56 fiscal years—or more than 90 per cent of the time.

Surpluses occurred from 1965-66 to 1966-67, 1969-70, 1989-90 and 2000-01. There was a 19-year run of deficits from 1970-71 to 1988-89, a 10-year run from 1990-91 to 1999-00 and a 20-year run from 2001-02 to the 2020-21, which is expected to continue. The sum of accumulated deficits over this 56-year period is $304.3 billion.

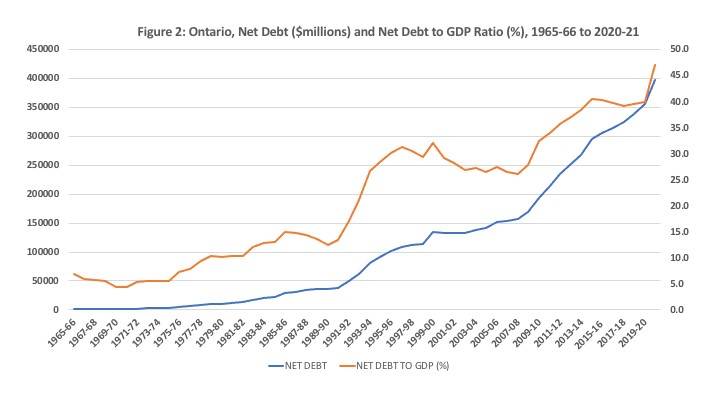

The second chart presents Ontario’s total net debt and its net debt-to-GDP ratio over the same period. Its net provincial debt has grown from $1.6 billion to $397.2 billion. As a share of the economy, the net debt was 7 per cent in 1965-66 and an estimated 47.1 per cent for 2020-21.

As the chart illustrates, much of the debt accumulation dates from the 1990s. Indeed, from 1965-66 to 1989-90, Ontario added about $34 billion to its net debt whereas since 1990-91, it acquired the remaining $362 billion. And you can’t blame high interest rates for the mounting debt because most of it was acquired after 1990 when interest rates began falling to reach current historic lows.

Moreover, the average annual rate of growth of Ontario’s net debt over this 56-year period has been nearly 11 per cent. If this rate was applied to a mutual fund return, Ontarians would be prosperous and richer than the dreams of avarice—but they are not. Per-capita income growth in Ontario has been lagging for the last 20 years and our appetite for increased government spending and borrowing is not sustainable given our poor income growth and productivity performance.

Ontario has faced deficits and mounting debt for decades. Again, the COVID- fuelled rise is really just part of an old pattern. Ontario’s large government debt is the result of chronic deficits that quickly mount during an economic downturn and then only slowly abate afterwards. While revenues and expenditures both rise over the long-term, spending growth has managed to outstrip revenue growth as recessions open up even larger gaps that then take years to close. During that period, debt mounts.

For example, over this entire 56-year period, real per-capita expenditures have grown at an average annual rate of 3.1 per cent while real per-capita revenue has grown at 2.6 per cent. But this includes periods of economic downturn when spending rises and revenues plummet.

However, when the analysis removes major recessions, real per-capita expenditure grows at 3.7 per cent while revenue grows at 4.9 per cent. Even with the rapid revenue growth of post-recession periods, Ontario is always playing fiscal catch-up.

The length of time taken after a recession to whittle down budget deficits means that by the time something approaching a balanced budget begins to materialize, the gap opens up again and the debt surge begins anew. Ontario has done the same thing over and over again for nearly five decades. It’s caught in a fiscal Groundhog Day and with the pandemic it would appear we have embarked on a new round of deficits and net debt accumulation that may dwarf what we’ve seen to date.