Trudeau government—and provincial governments across Canada—can learn from past fiscal consolidations

Introduction

Prior to the COVID recession, Canada faced significant fiscal challenges. These challenges were most severe at the provincial level. For example, Ontario had run uninterrupted deficits for over a decade, while Alberta had racked up $35 billion in debt over just five years.

The COVID recession has caused deficits to increase quickly and new debt to pile up. RBC Economics has forecasted that the pandemic will “spill red ink all over Provinces’ books.” In short the state of provincial finances have gone from bad to worse.

The federal government is now also getting into the game of rapid debt accumulation. Already running meaningful deficits before COVID-19, the federal deficit has soared this year due to the COVID-19 recession and the government’s policy response. More specifically, the Trudeau government’s recent fiscal update forecasted a $343 billion deficit this year, which is a larger deficit in nominal terms than the last 12 years combined. There’s no guarantee that such a large deficit will be eliminated quickly, which could mean much more federal debt accumulation in the years ahead.

Provincial finances are currently unsustainable and the federal government is facing rapid increases in debt. If they view deficit reduction as an important priority, policymakers will have to develop a clear plan for achieving it and remain committed to those plans over the course of several years. This blog provides a brief overview of Canada’s recent fiscal history to draw lessons that can help inform the difficult period of policymaking ahead.

International evidence on deficit-reduction—spending reductions or tax increases?

If governments accept the need for a significant fiscal consolidation in Canada post-COVID (a fiscal consolidation simply refers to shrinking the gap when government expenditures exceed revenues), the first question to be asked is whether it should be achieved by reducing spending or by raising taxes.

With respect to the impact of this choice on economic growth, there is evidence that shows a consolidation focused on spending reductions is preferable to one focused on tax hikes. Research by late Harvard economist Alberto Alesina and co-authors have shown that consolidations based on spending reductions are “much less harmful than tax hikes.” Although policymakers will have to balance a number of competing priorities in the years ahead, the evidence from Alesina’s work suggests that consolidations focused on the spending side of the ledger will be less likely to impede economic recovery than efforts to shrink the deficit through tax increases.

Fiscal consolidations in Canada Part 1—the 1990s

Alesina’s work looked at consolidations from 16 OECD countries. If we narrow our focus to Canada, we see that significant periods of fiscal consolidations from Canada’s recent past have generally been driven by reducing government expenditures relative to the size of the economy rather than increasing revenues. Specifically, in the next two sections we will show how reductions in government spending relative to the size of the economy drove the major fiscal consolidation period of the 1990s and the milder period of fiscal consolidation in the 2010s that immediately followed the global recession of 2008/09.

Let’s start by looking at the 1990s. Back then, Canada’s finances were on the brink of crisis. At the federal level, debt interest payments were gobbling up approximately 1/3 of all federal revenue. The need for change was best stated by then-finance minister Paul Martin who said in his 1995 budget speech “the debt and deficits are not inventions of ideology. They are facts of arithmetic.” In that same 1995 budget, Jean Chretien’s Liberal government began the process of a fiscal consolidation program that would ultimately put Canada’s finances back on stable footing.

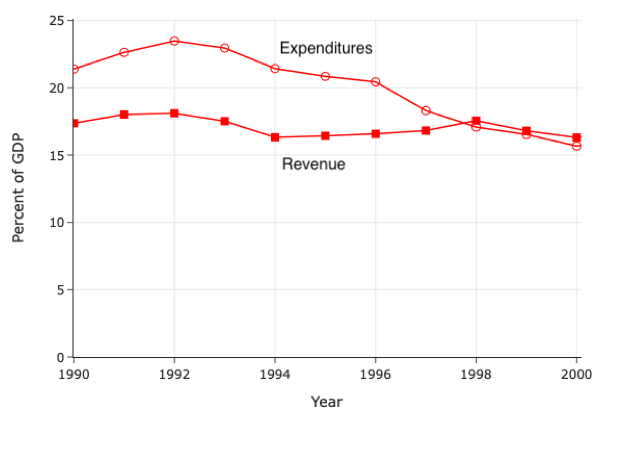

Although some minor tax increases were introduced, the fiscal consolidation of the 1990s was achieved almost entirely by focusing on the expenditure side of the ledger. The first chart below illustrates this reality.

Federal government revenue and total expenditures, 1990-2000

Source: Canadian Tax Foundation, Finances of the Nation REAL Dataset

In 1993, federal government expenditures as a share of GDP were 5.9 percentage points higher than federal government revenues. This translated into a $38 billion deficit. Similarly-sized deficits over the past decade were the reason for the large-scale debt accumulation and painful interest costs described above.

The chart above shows that the fiscal consolidation of the 1990s was achieved almost entirely via sending reductions. Specifically, between 1993 and 1998, federal expenditures as a share of GDP fell from 23 per cent to 17.1 per cent—enough to eliminate the 5.9 percentage point gap between revenues and expenditures that existed in 1993. Meanwhile, revenue as a share of GDP remained almost completely flat.

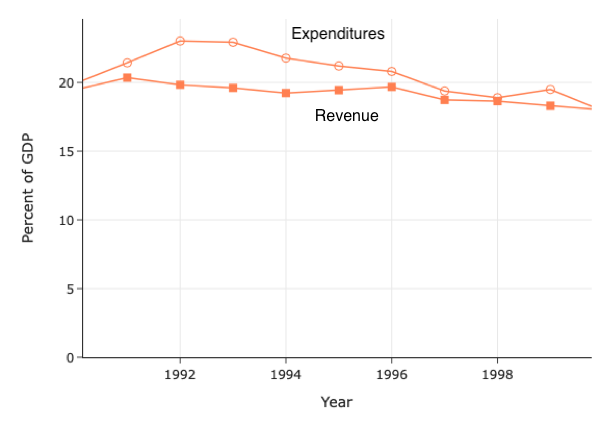

If we look at what happened at the provincial/territorial level (shown in the second chart below), a similar story emerges. In 1993, cumulative provincial and territorial government spending accounted for 22.9 per cent of GDP. This was 3.3 percentage points higher than provincial revenues, at 19.6 per cent. Provincial revenues actually dropped slightly over the course of the 1990s relative to GDP, but the spending reductions achieved by provincial governments across the country were nevertheless sufficient to return to balance. By 1998, the cumulative provincial/territorial budget balance was essentially zero.

Cumulative provincial and territorial revenue and total expenditures, 1990-2000

Source: Canadian Tax Foundation, Finances of the Nation REAL Dataset

It’s important to recognize that this impressive fiscal consolidation at the provincial and federal level was the result of efforts by governments across the country of a wide variety of political stripes.

Roy Romanow’s NDP government in Saskatchewan was, in fact, the first to make decisive efforts to eliminate the deficit by reducing expenditures. As we have seen, Jean Chretien’s Liberal government in Ottawa also followed this path. Meanwhile, Progressive Conservative governments in Alberta and Ontario shrank the size of their provincial governments relative to the size of the provincial economy sufficiently to eliminate severe deficits.

In fact, all four of these governments actually reduced spending in nominal terms during the fiscal consolidation period of the 1990s. In each case, the fiscal consolidation was achieved almost entirely via spending reductions as opposed to tax increases.

Fiscal consolidations in Canada Part 2—the 2010s

Although the fiscal consolidation of the 1990s was the most dramatic and famous in recent Canadian history, a second meaningful second fiscal consolidation (in terms of spending and revenue as a share of GDP) occurred throughout the early 2010s as governments across the country worked to reduce the large deficits that emerged during the 2008/09 recession.

Following global recession of 2008/09, several governments across the country faced substantial budget deficits. This deficit was the result both of revenue declines caused by the recession itself as well as spending increases at the federal and provincial levels that were intended to stimulate economic growth.

The outcome of these policy choices and the recession itself was the emergence of large budget deficits in the earl 2010s. In 2010, federal expenditures exceeded federal revenues by 3.2 percentage points of GDP. During this period, the federal deficit reached $56.4 billion. Meanwhile, at the provincial level in aggregate, the gap between revenues and expenditures topped out at 2.3 per cent of GDP in 2011.

In short, Canada found itself early in the 2010s once again facing the need for fiscal consolidation.

More precisely, almost exactly in line with the combined federal and provincial fiscal gaps described above, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), stated that Canada required a fiscal adjustment (combined at the federal and provincial level) of 4.7 per cent of GDP to return public debt to its pre-recession levels.

At the federal level, Stephen Harper’s Tory government achieved almost the entire fiscal consolidation necessary to eliminate the federal deficit over the period 2010 to 2015 when federal spending as a share of GDP was reduced by 2.2 percentage points while federal revenue as a share of GDP stayed essentially flat. As a result, as shown in the third chart below, by 2014/15, the deficit was reduced to $600 million, which is to say it was eliminated almost entirely.

Federal government total expenditures vs. revenue, 2005-2019.

Source: Canadian Tax Foundation, Finances of the Nation REAL Dataset

In subsequent years, increased federal spending as a share of GDP began growing again, leading to the re-emergence of meaningful deficits in the approximate range of $20-30 billion annually. This brings us to the present day, the COVID recession and the emergence of the historically large federal deficits described above.

At the provincial level, efforts at fiscal consolidation through spending reductions were somewhat milder. From its peak in 2011 a, aggregate provincial spending as a share of GDP gradually fell by 1.2 percentage points in 2015. This period of relative restraint was sufficient to shrink the aggregate provincial deficit, but not to eliminate it entirely. In subsequent years, spending as a share of GDP remained essentially flat, and so an aggregate provincial deficit remained. The small persistent fiscal gap was driven in large measure by sustained substantial deficits in Ontario. As such, the fiscal consolidations of the early 2010s are best characterized as having been only partly successful.

In total, the fiscal consolidations of the 2010s was milder, more gradual, and in important respects, less successful than those of the 1990s. The spending reductions of the 1990s were sufficient not only to eliminate larger deficits than those faced in the 2010s, but also were large enough to create fiscal room for pro-growth tax relief. Further, an extended period of mild spending restraint at the federal level in the years following the 1990s reform period meant that the federal had more fiscal room to weather the storm of the 2008/09 recession than many other OECD countries.

Indeed, the spending reductions of the 1990s and the extended period of spending restraint in subsequent years (including the mild spending-based consolidation of the 2010s) is still benefitting Canada today, as the country enters this new period of uncertainty and risk in a better fiscal position than most peer countries.

Conclusion

When the COVID crisis is over, Canada and most provinces will face large budget deficits. If they wish to prioritize eliminating those deficits quickly and avoid raid debt accumulation, they will require a concerted effort at fiscal consolidation.

Canadian history shows that large-scale fiscal consolidations are possible. In the 1990s, and to a lesser extent, the early 2010s, Canadian governments achieved meaningful fiscal consolidations. In both cases, the consolidations that were achieved were accomplished almost entirely by reducing government expenditures as a share of GDP rather than increasing revenues. In other words, the consolidations were achieved almost entirely by spending restraint and in the case of the 1990s meaningful outright nominal spending reductions rather than via tax increases.

While it's theoretically possible that governments across the country could achieve a nationwide fiscal consolidation via tax increases, there’s no recent historical precedent in Canada for doing so.

Further, Alesina’s international analysis of OECD countries suggests that attempting to eliminate provincial and federal deficits via tax increases would cause substantially more economic harm (and thereby make it even more difficult to eliminate the deficit) than a consolidation, such as those in the 1990s and early 2010s, based on spending reductions.

As Canadian governments work to eliminate daunting deficits and prevent the emergence of large-scale debt, they should consider our country’s history, which shows that spending-based fiscal consolidations are possible, and the international evidence suggesting that this approach (not tax increases) can achieve spending reductions at the lowest cost to economic growth.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.