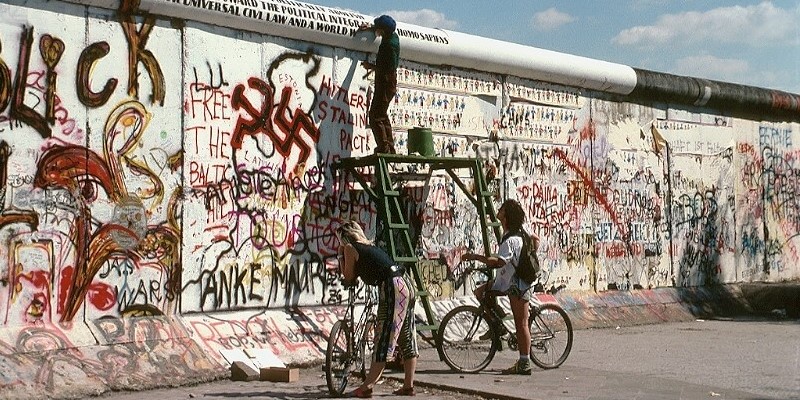

Still moving toward markets 30 years after the Berlin Wall

Last weekend marked the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, which was not only the start of German reunification, but one of several events that in the months and years to come would see more than 100 million people turn their backs to communism and steer their economies out of socialism and toward the market.

Prior to the fall of the Iron Curtain, the former socialist economies—to the east of the barrier dividing Europe—varied considerably in their degree of openness, soundness of institutions, economic growth and development. Similarly, these countries opted for different paths to market liberalization, some of them moving rapidly and with great strides to reform and liberalize their economies, while others to gradual transitional steps.

Today, 30 years later, unsurprisingly, public policies and political institutions of the former socialist economies do not equally support economic freedom. However, they support it to a greater extent than they did before the 1990s.

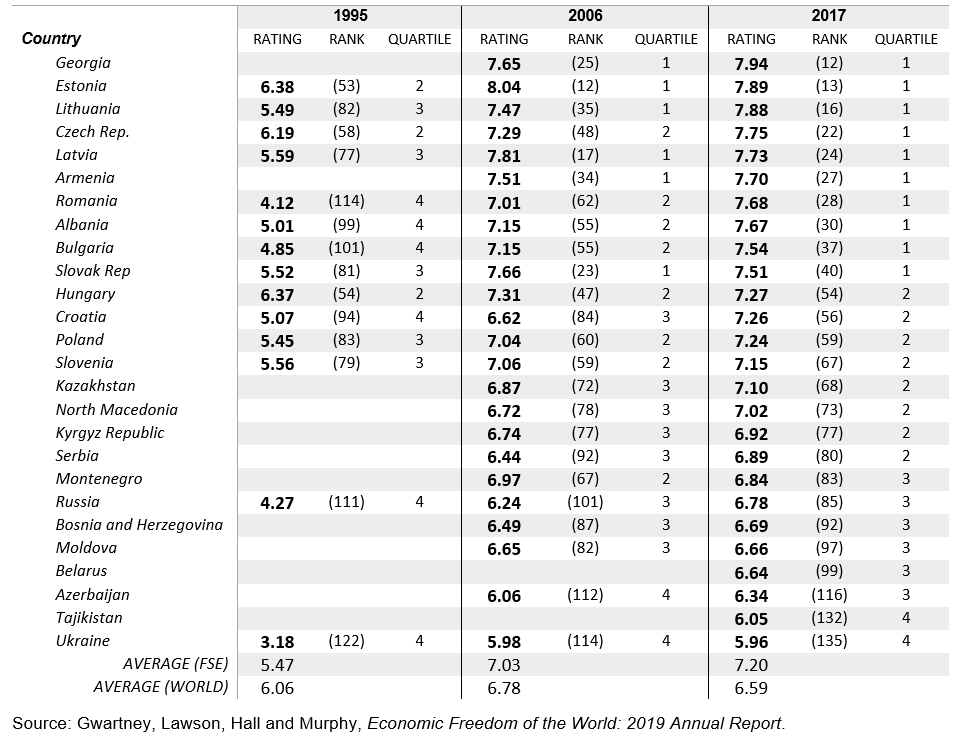

Providing a quantitative assessment of the degree of market liberalism, the Fraser Institute Economic Freedom of the World index finds that the highest levels of economic freedom in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia in 2017 (the most recent year of available data) were in Georgia, Estonia, Lithuania, the Czech Republic and Latvia while the lowest levels of economic freedom were in Ukraine, Tajikistan, Azerbaijan, Belarus and Moldova (see chart at bottom of page).

As the data show, all the former socialist economies in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia have strengthened their market features since the fall of the Iron Curtain. This sizeable and widespread transformation reflects the region’s embrace of private property, the rule of law, entrepreneurship, free trade, foreign direct investment and globalization. In the last few decades, economic liberalization has spread across the former socialist region at a higher pace than in the world, with the average degree of market liberalism in the former socialist economies (FSE) increasing from 5.47 in 1995 to 7.20 in 2017 compared to 6.06 to 6.59 in the entire world.

Moreover, in 1995 no former socialist economy ranked in the top economic freedom quartile, but in 2017, 10 of them (Georgia, Estonia, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Latvia, Armenia, Romania, Albania, Bulgaria and the Slovak Republic) were in the top quartile. By contrast, only two countries (Tajikistan and Ukraine) now rank in the fourth quartile of economic freedom while in 1995, six (Romania, Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Tajikistan and Ukraine) out of 14 former socialist countries ranked in the fourth quartile.

Several of the former socialist economies, such as Georgia and Estonia, have embraced economic freedom to such an extent that they have become true success stories of market liberalization by opening their markets, decreasing barriers to trade, lowering tax burden, stabilizing their monetary systems, deregulating and strengthening the legal system. By contrast, other former socialist economies have been unable or unwilling to increase their level of economic freedom. For example, Hungary observed the smallest move from socialism toward the market during the 1995-2017 period—however, it still increased its economic freedom score by 0.90.

At a time when nationalism and protectionism are emerging in many countries across the world, which only adds to downward pressure on the global economy, countries in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia should draw from their own experience and continue to reform and liberalize their economies. This will not only have positive impact on economic growth, foreign direct investment and the wellbeing of the citizens, but will also reduce poverty levels and economic inequalities more successfully than any other economic system.